[T]he Bach Choir represents a musical culture that was once a vital part of American life.I can’t verify the claimed link to heavy industry; after all, choirs today often tend to be filled with adults that have a love of classical music, which now is a decidedly elite orientation. However, from years of thumbing through my hymnal, I certainly recognize the links between the late 19th century choral renaissance in England and the US.

Post-Civil War America shared with Victorian England a love of choral music, and, oddly enough, choral societies and major choral festivals often sprang up in industrial areas like Leeds, Huddersfield and Birmingham in England's sooty midlands, American mill towns like Worcester, Mass., and places with large German-immigrant populations, like Cincinnati and Milwaukee.

Why this link between choral music and heavy industry? At that time, most industrial towns offered few pastimes for their working-class populace beside taverns and blood sports. Hence the founding of amateur choruses, with their regularly scheduled rehearsals, offered men and women an opportunity for respectable social interaction, combined with the positive aspect of learning and performing music.

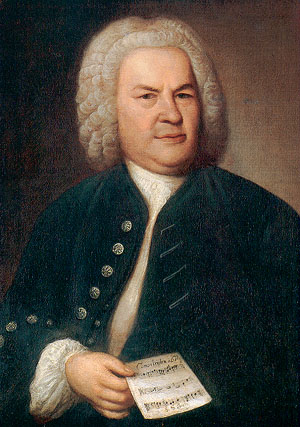

With my focus on “Anglican” (née Episcopal) hymnody, Scherer reminds me of the profound influence that Germans had upon both British and American hymnals (notwithstanding some ill-will between the two groups from 1914-1945). No one can dispute that J.S. Bach is the father of the four-part chorale, and some (including me) would argue its most sublime composer. While I haven’t whipped out my Piston to analyze those great 19th century hymns, from singing most seem to owe more to Bach than 19th century composers like Berlioz or Bruckner.

With my focus on “Anglican” (née Episcopal) hymnody, Scherer reminds me of the profound influence that Germans had upon both British and American hymnals (notwithstanding some ill-will between the two groups from 1914-1945). No one can dispute that J.S. Bach is the father of the four-part chorale, and some (including me) would argue its most sublime composer. While I haven’t whipped out my Piston to analyze those great 19th century hymns, from singing most seem to owe more to Bach than 19th century composers like Berlioz or Bruckner.The direct German contributions to Anglican hymnals are easy to measure. The composer index of the 1940 Hymnal lists 16 hymns by J.S. Bach — tied with R. Vaughan Williams and ahead of the entire Wesley family (mainly S.S. Wesley). It also lists 16 tunes under the category of “German Melody” (which have a publisher) or “German Traditional Melody” (which don’t), as well as 5 by Mendelssohn, 2 by Handel (a German in England), 1 by J.C. Bach, and various hymns from local Gesangbücher.

There is also the influence of Martin Luther — both upon the Anglican church and its music. Anglican churches perform a large body of Lutheran church music — beginning with Luther but also Johann Crüger (10 hymns) of the Berlin Nikolaikirche and then Bach with his chorales and sacred cantatas. Of course, 19th German immigrants to the U.S. created the German Evangelical Lutheran Synod (now Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod), the 2nd largest Lutheran group in the U.S. (but still larger than TEC).

I have yet to trace the flows of hymns between Anglican and Lutheran hymnals. In some cases, there are obvious direct linkages, as when Sine Nomine written for the 1906 The English Hymnal became hymn #463 in the (US) 1941 The Lutheran Hymnal. In other cases, there are common antecedents, as with so many Christmas hymns and probably most of the Bach.

Still, Anglican worship borrows a lot in both theology and liturgical music from the the Germans, something Americans (focused on our debt to England) tend to forget.

Credit: painting of J.S. Bach by Elias Gottlob Haussmann, as archived by Wikipedia.